Women’s rights do not tend to fare well during periods of political uncertainty. A shift to the right of the political spectrum, and the increasing normalisation and acceptance of small-c conservative political views, tend to go hand in hand with the retrenchment of women’s rights and curtailment of their bodily autonomy.

We know further that conservative political leaders who rely on conventional tropes of masculinity to shore up their authority – let alone those who openly boast in candid conversation of ‘grabbing’ women’s bodies without their consent – create a political environment in which women as individuals are not respected and feminine attributes are devalued.

The populism at issue here is definitely – as Wikipedia would have it – a politics of concern for the common man.

The populism at issue here is definitely – as Wikipedia would have it – a politics of concern for the common man.

I firmly believe that in order to bring about political change, we need to hold on to hope of doing better, thinking and knowing better, and to recognise that this might we mean thinking and knowing differently. In my own research and practice, I turn to the Women, Peace and Security agenda for inspiration.

Scholars and practitioners working on the WPS agenda, as it is known, address the gendered dimensions of international peace and security; the series of resolutions adopted by the UN Security Council under the title of ‘Women and peace and security’ have provisions related to the protection of women’s rights and bodies, the prevention of violence (including but not limited to conflict-related sexualized violence), and the participation of women in all forms of peace and security governance.

But its institutional architecture, within the UN Security Council, does not render this an elite political project. Those who work in this space have deftly demonstrated the danger in assuming that peace and security knowledge is produced only by particular peace and security elites.

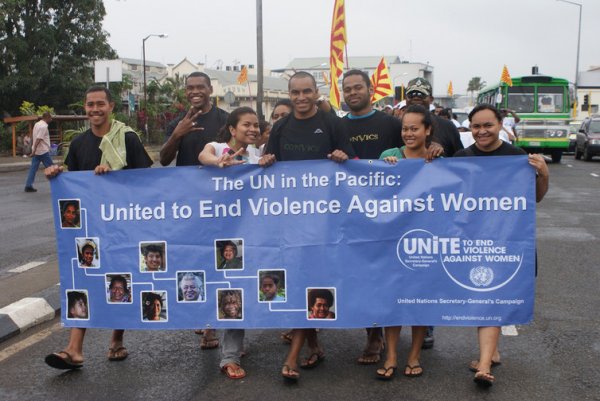

Groups like UN Women, with the support of Australia’s Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, work to end violence against women in conflict zones. Image: CWDL

They have sought to redefine the peace and security ‘expert’, showing that we need to pay attention to the emergence of different kinds of political actors. A different kind of populism, one that subverts the boundary between everyday people and elites in different ways, can enable us to recognise these everyday peace and security actors as theorists of a different world.

In her analysis of the advocacy practices of women’s human rights activists, Brooke Ackerly shows that they are always-already ‘cross-cultural theorists’. In my view, these actors – including but not limited to academics, activists, advocates and artists – are plural and diverse experts, theorising different worlds.

We need to pay attention to the emergence of different kinds of political actors.

These actors don’t necessarily inhabit textbooks (although some do, as illustrative cases in textboxes or figures, or even as chapter authors themselves), they are not necessarily tenured academics (although some are) nor do they necessarily speak the language of the academy (although some do).

But these political actors are well placed to teach us about how a politics of the everyday – a populist politics of a different sort – can be inclusive and productive rather than exclusionary and destructive.

The continuing quest to realise women’s rights and their full and meaningful participation in peace and security governance is further embattled in this ‘age of populism’.

In the context of such diverse and various societal fissures, fractures, and failings, I propose that now more than ever women’s peace activists and human rights activists deserve recognition as legitimate ‘knowers’ in and of world politics.

Now more than ever women’s peace activists and human rights activists deserve recognition as legitimate ‘knowers’ in and of world politics.

The violations of women’s rights and bodies made possible by the steady erosion of the preventative and protective measures applicable to those rights and bodies will be felt most keenly by those women and allies working in and through the spaces that are frequently invisible to conventional studies of peace and security.

These are the ‘ordinary people’ whose concerns and voices should be heard. This is the populace whose everyday politics should inform our thinking and our activism.

These are the peace and security experts to whom we should pay heed. These are uncertain, precarious, and dangerous times for so many people, and we cannot think of change if we do not change our thinking.